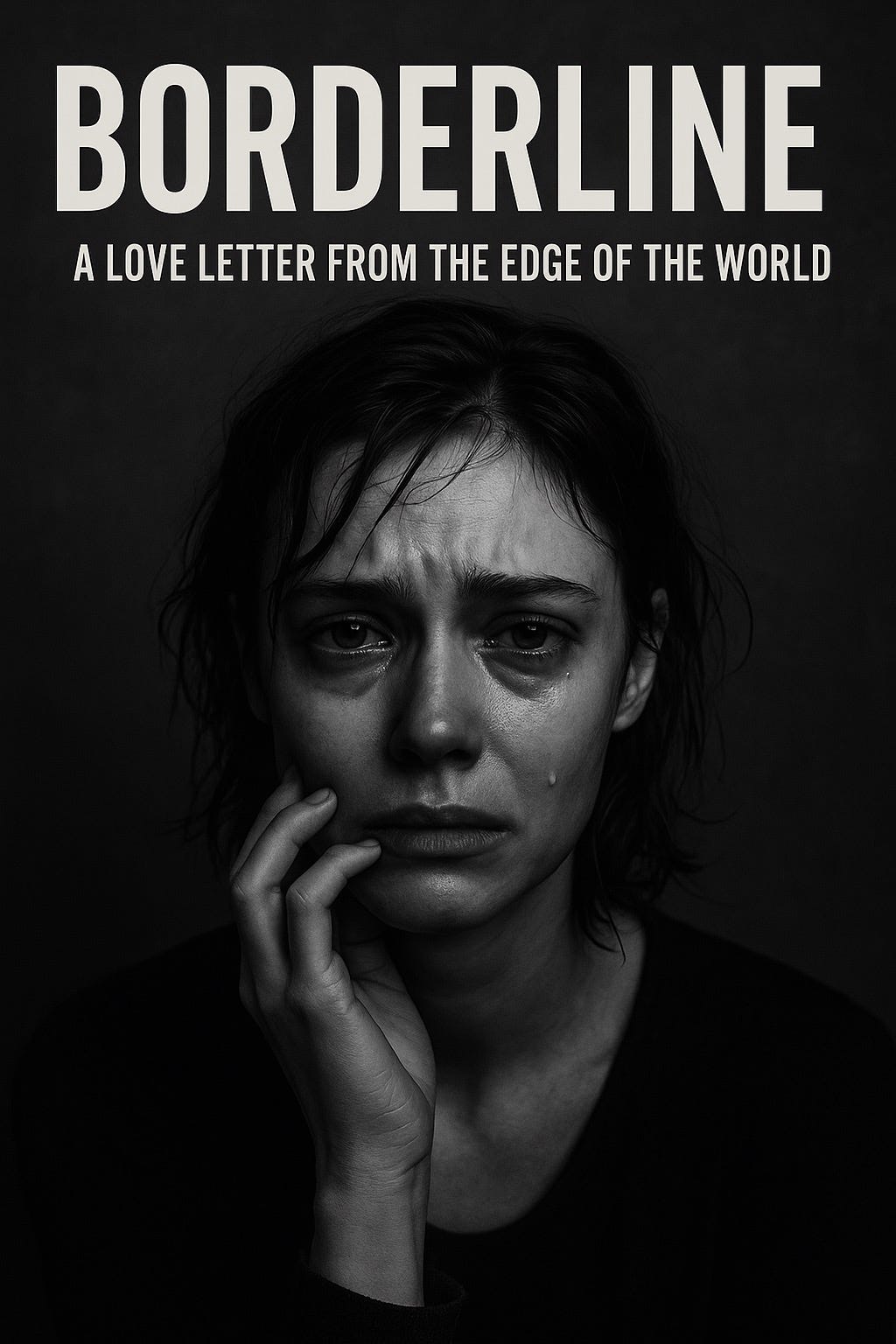

There are diagnoses that name you.

And then there are diagnoses that consume you.

Borderline Personality Disorder is the latter. Not because it is inherently monstrous, but because of what it mirrors, what it holds up to the light. It is the name the world gives to people like me when our pain can no longer be contained in palatable ways. When we bleed too loudly. When we want too much. When we survive in ways that are inconvenient for others.

To be labeled “borderline” is not just to have a diagnosis. It is to inherit a stigma so powerful it can eclipse your entire humanity.

And yet—I would be lying if I said I didn’t find pieces of myself in that word.

Borderline: on the edge of being.

Borderline: in-between.

Borderline: a flickering, shapeshifting self formed in the aftermath of relational ruin.

This is not just a disorder. This is the psychological residue of living too long in the in-between spaces—between love and violence, between safety and danger, between who I was allowed to be and who I really was.

The House Built From Hunger

I was not born broken. I was born hungry. For affection, for attunement, for someone to see me and say, “Yes. You make sense. You matter.”

But that is not the language I was raised in.

Instead, I was fed the scraps of love and called it a feast. I learned to shape-shift to avoid punishment. I learned that crying too long would lead to silence. That anger would get me hit or left. That joy was a liability, easily taken away.

Borderline is not a personality disorder.

Borderline is a grief disorder.

Borderline is the body’s rebellion against being unseen, unheard, unfelt for too long.

We learned to scream because we were ignored.

We learned to cling because everyone left.

We learned to split because black and white was the only safety our nervous systems could find in a world that never gave us grey.

People call us manipulative.

But tell me—what is manipulation if not the language of a child who has never been taught to ask for what they need safely?

People call us dramatic.

But tell me—what is drama if not emotion finally unbound, finally unhidden, finally allowed to speak after decades of silence?

Living in the Borderlands

Imagine waking up every day in a body that doesn’t know the difference between heartbreak and apocalypse.

That’s what BPD feels like.

Love feels like threat. Intimacy like a knife pressed to your throat. Every goodbye feels final. Every silence feels like abandonment. Every glance that lingers too long—or not long enough—is evidence that you are too much, or not enough, or both at the same time.

I have begged people not to leave while simultaneously shoving them away.

I have cried on bathroom floors because someone didn’t text me back in time.

I have fallen in love with people I barely knew because, for a moment, they made the emptiness stop.

BPD is not being unstable.

It’s being hyperstable—in our patterns, our pain, our desperation. We loop. We relive. We repeat. Because our brains are trying to solve a puzzle with missing pieces.

It is living in a haunted house, and the ghosts are versions of yourself you were never allowed to become.

The Myth of the “Difficult Woman”

Let’s speak plainly.

BPD is a gendered diagnosis.

It is weaponized most often against women.

It is a psychiatric scarlet letter that says: this woman is too emotional, too reactive, too needy, too sensitive.

I have sat in rooms where clinicians labeled women with BPD simply because they cried too much, or wanted too much from their therapist, or had “boundary issues” because they’d never been taught how to hold themselves.

I have read notes that said “attention-seeking” when what they meant was: “She is begging us to see her pain, and we don’t know how to hold it.”

Here’s the truth: there is no such thing as attention-seeking behavior. There is only connection-seeking behavior in people who have been repeatedly denied connection.

We are not “bad patients.” We are deeply traumatized people with relational injuries so profound they shape the architecture of our identity.

Rage, Shame, and the Longing Beneath It All

The core wound of BPD isn’t just abandonment.

It’s the shame that grows in its wake.

I am ashamed of how much I feel.

Ashamed of how quickly I fall apart.

Ashamed of the way my voice cracks when I ask, again, “Do you still love me?” even though you said yes five minutes ago.

The rage that people see in us is not cruelty. It’s protest. It’s the howl of a child who was never comforted. It’s sacred fury, distorted by years of having no safe place to land.

The worst part? We turn that rage inward.

We don’t just fear losing others.

We fear we are fundamentally unlovable.

And yet—we keep loving. We keep trying. We keep showing up in therapy, in relationships, in life. We hold so much hope inside these broken-seeming bodies, even when the world keeps telling us we are impossible to love.

Healing is Not Linear. It’s Liminal.

Here’s the part people don’t tell you: recovery is possible. But it’s not clean. It doesn’t look like a straight line.

It looks like learning to pause before the text, the scream, the cutting, the spiraling.

It looks like breathing through the panic that comes when someone takes too long to reply.

It looks like slowly, painstakingly, building an internal self that can hold your own pain instead of outsourcing it to others.

It’s not glamorous. It’s not instant. But it’s sacred.

I’ve learned to mother myself.

To witness my feelings without shaming them.

To sit in the fire and not burn down the house.

It’s still hard. Every day. But it’s not hopeless.

If You Love Someone With BPD

You will not save us.

But you can be a mirror.

A steady, honest, compassionate presence. Someone who doesn’t run when we panic. Someone who reminds us, softly but firmly, that we are still here. Still held. Still real.

You will need your own boundaries. You will need support. But please—don’t dehumanize us. Don’t reduce us to “crazy,” “toxic,” “borderlines.” We are people. With nervous systems that have been through war. And all we want, at the end of the day, is to come home to ourselves.

Sometimes we just need someone to hold the door open.

My Name is Not Borderline

I am not just my diagnosis.

I am a survivor of trauma.

I am a mosaic of grief and grit.

I am a lover, a writer, a friend, a fighter.

I have sat in the center of my own ruin and chosen, again and again, to rebuild.

And I will continue to do so, even if my hands shake. Even if my voice quivers. Even if the world never stops calling me too much.

Because I know now: too muchness is not a flaw.

It is evidence that I am alive. Still feeling. Still reaching. Still here.

And that, my love, is a miracle

Whitney, you did it again. You shouted your truth out loud! Not worrying about one damn thing. BPD is tough. But you? You are tougher! Bravo! 💕

“Borderline is not a personality disorder. Borderline is a grief disorder.” Well said, all of it! As a Radical Behaviorist, we see psychiatric disorders as ways to categorize behavior that doesn’t fit the mold, using the medical model of pathology. I’m not big on this practice or diagnostic labels for what is ultimately just behavior, though getting a diagnosis can lead to getting help fitting into and accepting a broken system. But the “personality disorders” class of diagnoses has always rubbed me the wrong way. “Personality” is just a way to classify behavioral patterns, all of which are acquired and maintained by the external environment. The obvious problem with the personality diagnoses is that they’re saying “these patterns are your fault; something is wrong with you.” And that doesn’t help the person or point to the true causes that could be addressed, especially when it comes to “BPD.” Also, like you said, “Borderline” is disproportionately diagnosed in females, which suggests there are common experiences that lead to similar behavioral patterns amongst females, or that the “disorder” is based on women behaving outside the lines of a male-defined culture. And the alternative “emotional regulation disorder” isn’t much better. I’ve heard it suggested that, many times, “borderline” is ADHD and/or Autism + CPTSD, which makes sense if you’re tied to the medical model. But, I am not keen on pathologizing behavior as a problem of the brain or inner workings. I think you’re onto something with grief and trauma, and wanting to be loved for who you are (rather than who you’re being, for them). I do not have this diagnosis but I relate to some of the things you said here: the grief of not being loved or seen, trauma, or an environment that has lots of punishment and aversive control, emotional responding when people don’t reply, getting attached and loving too hard when someone finally sees you (until they inevitably leave, too). In short, I loved this piece. Thank you. “It looks like slowly, painstakingly, building an internal self that can hold your own pain instead of outsourcing it to others.” 💕 I’m just not sure that’s possible without others.